They say you can learn more from failures than from successes. But that doesn’t seem to be the case when it comes to publishing academic papers. While successes are often widely celebrated, failures are rarely publicized. In this blog post, I would take the less-traveled path and talk about what I have learned about academic publishing from four rejections of our ForestIV paper. The idea behind this paper was initially developed during my final year in the Ph.D. program, but it took 4 years to publish it in INFORMS Journal on Data Science. During this prolonged journey to publication, it was rejected by PNAS, Management Science (twice), and Journal of Machine Learning Research (after 3 rounds).

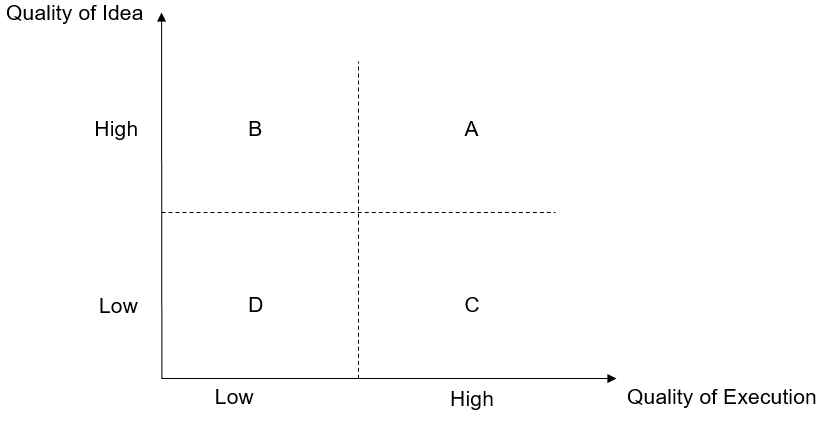

To help articulate my reflection, let me put academic papers into the following 2 by 2 matrix, based on the quality of idea discussed in the paper (i.e., how novel / new the idea is) and the quality of execution (i.e., how rigorous / meticulous is the execution).

Papers in categories A and D are easy to judge - A-type papers should clearly be accepted and D-type papers should clearly be rejected. However, what happens to papers in categories B and C are not immediately clear and ultimately reflect how journals handle the tradeoff between idea and execution. Our ForestIV paper (in my biased opinion) falls into category B. While it has a very unique idea (the novelty / quality of which has been consistently acknowledged during the review process), its execution is imperfect, due to the difficulty of theoretically analyzing data-driven machine learning models and procedures. The fact that it has been repeatedly rejected at respected outlets made me understand (perhaps in a cynical way): good execution of an incremental idea will have an easier time in today’s academic publishing than imperfect execution of a novel idea.

Although this may have been obvious to some, it was not to me. While trying to make sense of it, I came to the realization that the objective of the peer review process, paradoxically, can be at odds with the goal of scientific research to promote novel ideas and to have others gradually build upon those ideas. The objective of reviewers is to scrutinize a paper and produce a report. Focusing on the execution allows a reviewer to write a comprehensive report that shows both expertise and effort, whereas focusing on the idea could be subjective and more distant from the technical trainings that many reviewers have received.